On the Origin of Fursonas

Your personal fur is who you are when you take OFF all the masks

– Rod O’Riley, quoting Mark Merlino

When Mark Merlino, a.k.a. Sy Sable, passed away on February 20, 2024, furry fandom lost one of its greats. I attended Rod and Mark’s Two Old Furry Fans panel at PAWCon, 2023, in San Jose, where someone asked how furry has changed over the years. The biggest change they had witnessed, Rod and Mark said, was the development of the personal furry and the fursona (related but distinct terms, as we shall see). In the early days of furry, folks tended to use their real names and create external characters—something you can see reflected in furry archival materials from the 80s and 90s. Over the 90s and early 00s, however, furries increasingly created fursonas.

So what, exactly, is a fursona? As I learned in the course of researching this article, that “exactly” is the crux of the problem. You get to define your fursona (or fursonas—why stop at one?). You get to decide how, exactly, they relate to your … shall we say, human sona? Wikifur defines “fursona” as “a (normally furry) character, persona, alter ego, avatar, or identity assumed by a person or player normally associated with the furry fandom” (Wikifur, “Fursona”). When Merriam Webster added “furry” to their 2016 “Words We’re Watching” list, they similarly emphasized how fursonas can represent a range of identifications. Some folks just roleplay as their fursona online; others might have badges, or paws and a tail; others might fully identify as their sona (Merriam-Webster, “What is a Furry?”). And let’s not forget that many fursonas have no fur at all, but rather scales, feathers, exoskeletons, and even bio-cybernetics (looking at you, protogens)!

In an essay published in Queer Studies in Media & Popular Culture, Hazel Ali Zaman argues that more important than what a fursona is is what a fursona does:

Through various openly queer spaces online, where minoritarian subjects could find refuge together as fugitive subjects, I learned to embody fursonas that would end up giving life to parts of me I thought were not previously possible. In other words, the life-giving force I pursued to create and embody a fursona opened a world of material possibilities for my own queer of colour life through a collective coming together in difference with other queer and trans people who are also furries.

(Zaman, 100)

Croc O’Dile similarly emphasizes creating a fursona as a form of self-expression that crosses the boundary between our imaginations and what we often call the “real world” as if the works of our imagination were somehow less real:

Getting a fursona is like getting a brand new canvas, a new block of wood. Maybe you’ll draw a sketch. Maybe you’ll ink it. Maybe you’ll make it 3D, or make it into a film. ‘Fursona’ doesn’t imply shallowness or depth because the potential lies with the individual. It’s what the individual makes of them. […] It’s also a tool of self-exploration. You’ll learn things about yourself as you learn about your character. Being furry is the first step in ‘I can construct myself in a way that feels true to me.’

(Croc, interview)

Even as it means different things to different people, making a fursona is nowadays practically a rite of passage in furry fandom. It wasn’t always this way, however. What did furries call themselves before this term became popular? When, for that matter, did furries start identifying with or as their characters? How did the idea of the fursona evolve? This article explains the early evolution of a now-ubiquitous concept in furry fandom.

1980s. Avatars: From Playing to Being

The word “fursona” didn’t exist in the 1980s. But the concept behind the fursona — an OC who on some level represents their creator — has its origins alongside the emergence of furry fandom itself.

Who created the first fursona? Two answers: 1) Ken Sample; 2) it’s complicated. There are two reasons it’s complicated. First, we’re dealing with the origin and evolution of a concept whose meaning has shifted over the years and across media. In the 80s and early 90s, those media included everything from sketchbooks to room parties, MUCKs to APAzines (and, since then, so much more). So it’s fair to say that the evolution of the fursona has always been a collective enterprise of meaning-making.

Second, there is the terminology problem. Today, “fursona” means something a little bit different for everyone since everyone relates differently to their sona. Similarly, in the context of the nascent furry fandom of the 80s, the lines between creating a furry avatar vs. playing furry characters vs. identifying as one’s character “get kinda … fuzzy,” in Yippee Coyote’s words (Yippee, interview).

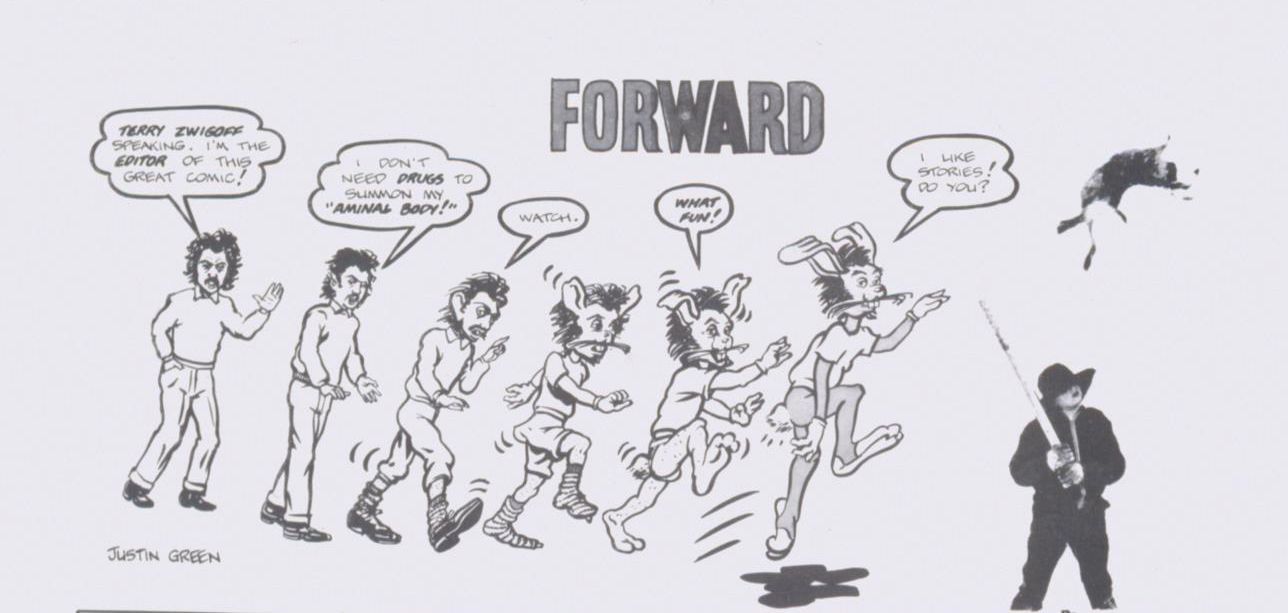

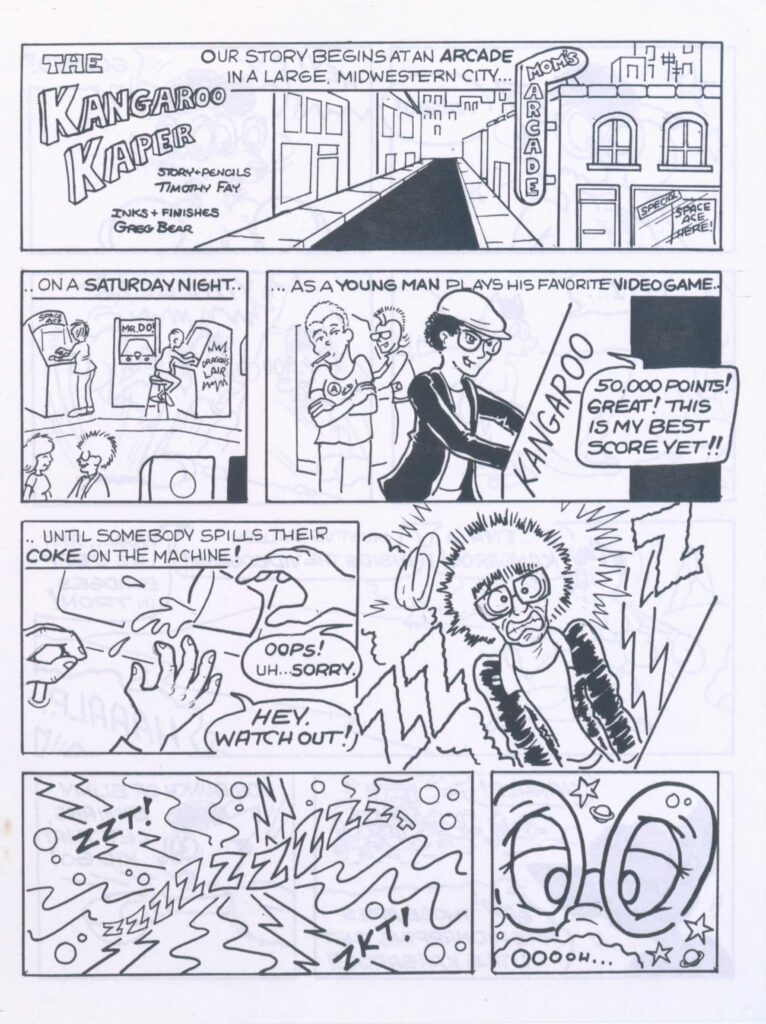

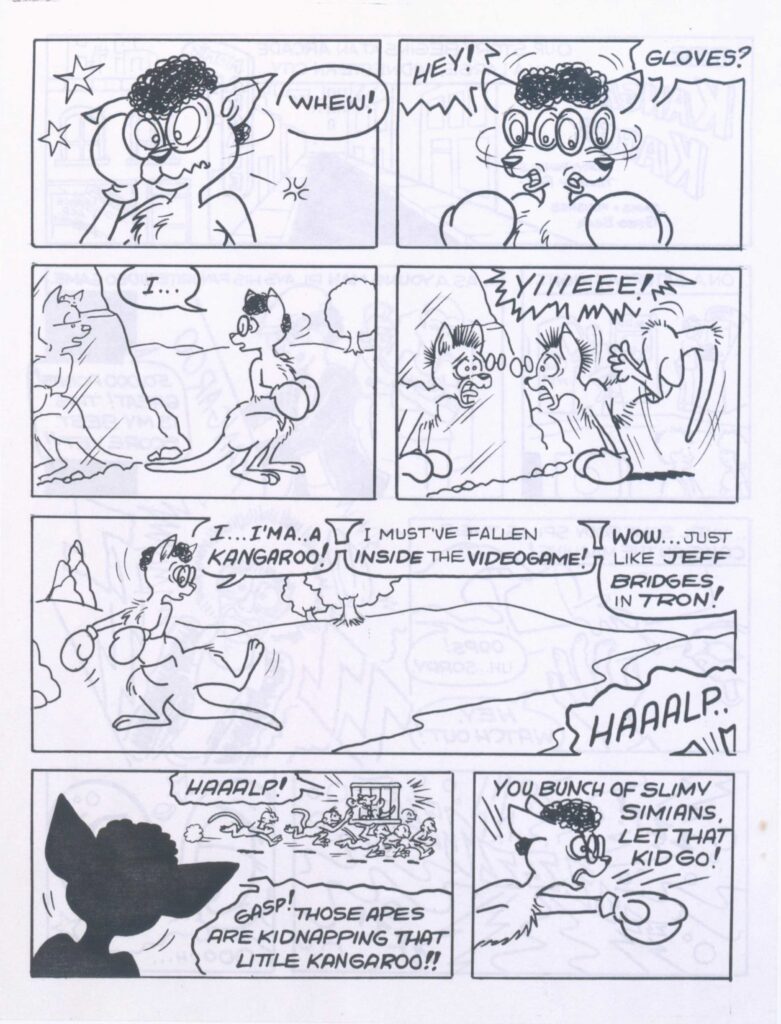

For example, Joe Strike reports in Furry Nation that Bulletin Board Systems – a.k.a. BBSs, a form of electronic communication that involved connecting to another computer via modem – “were the first opportunity for furs to present themselves as their fursonas to others” (178). But since it’s difficult to find archival records of early furry BBSs, it’s hard to say whether anything resembling fursonas ever appeared. Xydexx Unicorn remembered contributing to a BBS that may have been called “The Dragon’s Myth” in the 914 area code – and that was run by a dragon! (Xydexx, interview).1 But was that a dragon-sona or just an alias? For that matter, what about the 1972 Funny Aminals [sic] anthology comic, by Robert Crumb (et al.), where editor Terry Zwigoff is portrayed summoning his “animal body”? Or Timothy Fay and Greg Bear’s “Kangaroo Kaper,” a comic from Rowrbrazzle 3 (1984) featuring a young man who learns to embrace his ‘roo side? Or James E. Babcock, who in the preface to his comic submission for Rowrbrazzle 10 (1986) wonders aloud what it would be like to live among insects? (Shout-out to Brandy J. Lewis for teaching me about and helping me access these sources!) When does a character become a ‘sona?

That’s why who created the first fursona? is a tricky question. Based on the evidence we do have, however, it’s also accurate to name Ken Sample (a.k.a. Ken Coug’r) the originator of what we now call fursonas because Ken was the first identifiable person drawing himself and his friends as furries (as opposed to simply depicting their OCs).

The creators of the 2020 documentary, The Fandom, also name Ken Sample as the originator of the fursona. That was a big deal, but some furries criticized the film for not digging more deeply into this history. “As a Person of Color,” Weasel writes in a review of the documentary, “that’s a monumental detail for me. It tells me that Furries of Color are important, are necessary, yet the treatment of this detail also tells me it doesn’t matter to furries’ perceived self-history” (Weasel).

In writing this article, I had an opportunity to speak to Ken about being given the title “Creator of the Fursona,” and I feel it’s important to provide the context as Ken explained it to me:

Please understand that I am still unsure about the creation of fursonas thing that’s been placed on me. I spent, like, two weeks after that announcement trying to find examples of fursonas before mine. I wasn’t successful, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t out there. It’s a lot to take in. Still.

(Sample, interview)

Ken explained to me that between the fact that we don’t have a complete record of early furry history and the fact that terminology changes (“I gave you my interpretation of fursona. My friends have a slightly different one”), he felt uncomfortable being titled “Creator of Fursonas” but also agreed that he may well have been the first to draw furry avatars in the nascent furry fandom (Sample, interview). That is in line with what I found in my research.

The more important point that came out of our conversation, though, was de-emphasizing the idea that fursonas came from a single origin point. Whether he was first didn’t matter to Ken so much as the overall evolution of the term — the move, as Sy and Rod noted in that panel at PAWcon, from playing a character to being a character. Before fursonas,

I think the prevailing attitude about personal characterizations was to adopt the personality and traits of a favorite character and role-play that character. I suppose the term “avatar” would be best. The person would be a werewolf, or an alien or mythical being that was a character. The being wasn’t them. The being was someone they pretended to be.

(Sample, interview)

People would, and still do, take to copying the look or background of a character, changing the look or background enough to be more their own. An example that comes to mind is a friend of mine who adopted Steve Gallacci’s Erma Felna, from his “Albedo” comic as their avatar. It wasn’t exactly Erma, but it was Erma. Over time, the avatar evolved to be a different entity and a personal furry.

This movement from playing to being can be seen in the story of Ken Coug’r. In the first episode of Merlino’s and Rod O’Riley’s Two Old Furry Fans podcast, Merlino reflects upon Sample’s art from the 1980s. In addition to doing the official design of Anima, the mascot of the of the Cartoon/Fantasy Organization’s New York Chapter, Sample drew big cat characters.

One of the characters that started showing up in a lot of his art […] was a cougar, with kind of an afro, that represented him, although he didn’t actually give the character a name. It was just another character for him to draw to react to his other characters. I and several of my friends thought, ‘this is obviously a version of Ken. I had not met him at the time. When I met him years later, I realized that in fact it was a pretty good interpretation of Ken turned into a young adult cougar person, and we started calling the character Ken Coug’r. He never did, at that point, admit it was supposed to be him, but it was pretty obvious.

(Merlino and O’Riley, podcast)

In our discussion, Ken confirmed this point about Coug’r:

He is -the- representation of me as a furry. I used to draw my human self in relation to furry characters. I eventually got it in my head that it would make more sense to actually be furry me. Besides, Coug’r is more fun to draw.

(Ken Sample, interview)

Inspired by Ken’s furry depictions of his friends, Merlino “decided to start designing characters to represent my friends and roommates,” such as Andre Tiger for Andre Johnson (Podcast, 6′:00″-9′:30″). The idea of representing oneself or one’s friends as an animal was, in other words, a bit of harmless fun, and since little extra meaning was attached to these representations, folks called them avatars. “The concept was ‘what we think we would look like as our preferred animal’,” Wolf Kidd explained to me, “which is why most of them are relatively mundane looking and minimally idealized. Their purpose was to allow us to interact as furries in fan-fic, stories, fan-art, drawings and comics” (Wolf Kidd, interview).

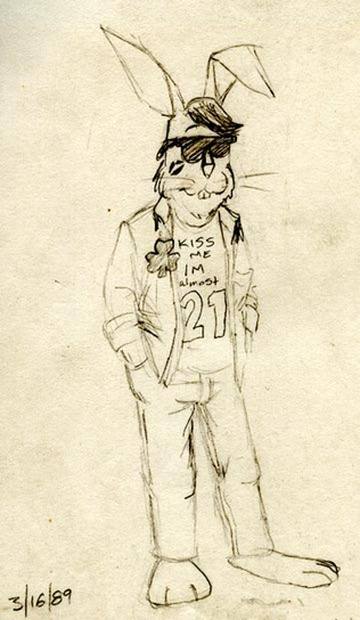

It might not seem like much, but the door was suddenly open, and furry avatars started appearing in different places, from FurryMUCK to Furversion. For instance, this ad in Fuversion 5 is ambiguous about where the line is between a furry character and their human creator:

Wolf Kidd told me that “Ken and I have always joked about how boring our avatars are, because they’re ‘just us’.” But this concept “quickly evolved into what people *wanted* to be, increasingly more idealized and fantastical which is when the term started to evolve into ‘personal furry’ because the characters stopped being furry representations of the person’s real-world physical self” (Wolf Kidd, interview).

And so we arrive at the next chapter.

Late 80s & early 90s. “Personal Furries” and the Power of Fantasy

Now, this is where things get a little confusing. When a new word enters the language, it doesn’t always settle into a stable meaning. Per Wolf Kidd’s insight, personal furry, for some, signified something more than a furry avatar; it was an idealized or fantastical furry self. A want rather than “me but as a furry.”

For Yippee, by contrast, the personal furry was similar to an avatar. “I think personal furry came from a different headspace than fursona, just a way to portray yourself in furry art, like an avatar” (Yippee, interview). So too Ken Sample:

A personal furry is the role-play avatar. The heroic star fox that’s come to your world to see what the inhabitants are like. The huge dragon living in the ancient mountains guarding his horde from adventurers. A personal furry can also be a character you created for a story and decide to play as in public settings.

(Sample, interview)

Fairlight/Dusk explained that, for him, Fairlight started as an avatar, but then when he got his Dusk suit, he tended to go by Dusk. “It’s just another label on what is still just me underneath” (Dusk, interview). So in other words, “personal furry” could range in meaning from a roleplaying avatar, to a furr-ified version of one’s human self, to an idealized furry self—which is one sense of today’s term fursona.

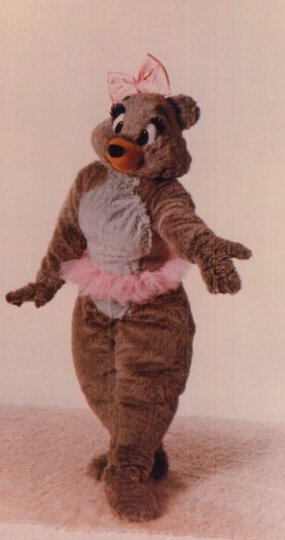

During my interviews, the meanings of these terms were not stable. Add to that the fact that new furry forms were blurring the lines between character and self in other ways. For instance, Robert Hill’s early fursuits, such as Annabelle Bear (1987) and Hilda the Bambioid (1988), imagined fursuiting — at the beginning of furry fursuiting history — as a cute and sexy expression of an individualized character. How much of that was a matter not just of playing but of becoming the character? In an interview, Hill speaks of himself as a “performer” yet also cites the inspiration of Rocky Horror Picture Show’s Dr. Frank-N-Furter: “Don’t dream it – be it!” (Hill). Suiters out there know that it’s hard to be in suit and not, on some level, identify with the character you are portraying.

Yet this ambiguity of terms and meanings is itself a testament to the furry spirit of creation and evolution: we create an idea (or an art style, a medium, a MUCK, a location on the internet), and we run with it. Some things have an incredible run but eventually fall out of fashion, as happened with many furry print publications. Other things evolve and change shape.

The notion of “personal furry” that Wolf Kidd describes — i.e., the character who represents something more, something deeper, something desired — did take hold at precisely the time when furry fandom was proliferating into different spaces and media, including Confurence, print publications like Rowrbrazzle and Furversion, FurryMUCK (a.k.a. FM), and Usenet newsgroups (such as alt.fan.furry). FurryMUCK user Axiom explained that before FM,

People were desperate for visible media. The cons brought people together to exchange/buy. Artists began to have not so much mailing-list circles, but ‘sketch book’ circles. They’d go to cons, hold room parties with fellow artists, draw in each others’ sketchbooks (always those big black covers!) and swap. Those books exist now as records of that time, and are full of idiosyncratic, one-off, never seen outside the five people in that room repositories of (usually naughty) artwork. Often of FURSONAS.

(Axiom, interview)

FurryMUCK, which opened to the public in 1990, gives a great lens into what the personal furry made possible. FurryMUCK was (and still is!) a text-based virtual reality world where users could log in and interact in pre-built locations composed of verbal descriptions. To log into the MUCK, you would create a character by naming them, writing a physical description, and even (if you so desired) creating a personal scent! (Benedikt and Ciskowski, 77). Early user Siege said, “I’d spend time in a blend of in- and out-of-character states. […] I think a lot of folks were simply trying on ways to relate to themselves and each other, much as it turned out I was” (Siege, interview). Dralen Dragonfox told me, “In Character/Out Of Character was always such an individual thing. There was always a gap between the ‘Personal Furries’ where your fursona was just you but as a furry, and the RPers who were always in character” (Dralen Dragonfox, interview).

In a comment on a Blog post, user BunnyHugger comments,

Back in about 1994, my main character on FurryMUCK carried an object that said BUTTON: I am a personal furry, which was something I had seen others do and copied. It meant that this specific character was the one you used as your self-representation. It also carried the connotation that this character had no IC mode because it was just your avatar for chatting with other people on the MUCK. It was a warning that you would be OOC all the time.

(BunnyHugger)

FurryMUCK, in other words, was central to the evolution of the personal furry concept, and what made it so powerful was its text-based nature. As Axiom elegantly put it, to “swim in text and love its freedom … well. It’s like a drug, that freedom, that ability to be someone else, something else.” Axiom told me about creating his first ‘sona, Keats (“the first greyhound in all Furrydom, as it turns out!”), whom he described as a bodily fantasy that crossed real and furry worlds. Text was freedom in part because it wasn’t embodied in the way fursuits are; you could be anything that you could put into words.

The moment I created Keats, the quiet, ultra-slender, mature (he was mid-20s to 30s), erudite Professor of English, complete with tweed jacket and briar pipe (only for show, I loathe smoking, even in fantasy!), he was a picture of ME as I HOPED I COULD BE, as a promotion to the instant realization of all my goals.

(Axiom, interview)

So it was a reflection of what I wanted to be, what I thought was ‘success,’ what I thought was attractive — because *I* found it attractive. Thin, wealthy enough to have a home packed with books and a nice fireplace, cozy, wood-paneled cottage off the busy areas, but not quite secluded. Keats would invite friends over and talk poetry, music, novels, sipping fine spirits and acting like something out of an Evelyn Waugh novel (without the acid).

So this is the simplest and most common […] form of the fursona: a reflection of what a person wishes they were, or are striving for. You get this ALL the time.

FurryMUCK is a great example of how, in the late 80s and early 90s, the concept of the personal furry opened up fantasies of selfhood and interaction with others. And the fact that furries were so quickly adapting to different print and electronic and 3D media only meant that these fantasies had more range to stretch the imagination.

A good example of this — and adding to the terminological confusion — was Avatar Archive (a.k.a. The Furry Art Archive), an FTP site by FurryMUCK wiz S’A’Alis that was used to gather images of characters who lived in FM (Wikifur, “Avatar Archive”). An Historical Avatar Archive Mirror is still accessible online.

Similar discussions around furry self-creation were happening on Usenet in the early 1990s. Alt.fan.furry, a newsgroup created shortly after FurryMUCK, was a place where users could post and respond to threads, and within its first year of existence users were asking for an FAQ to help clarify some furry terminology. That FAQ came in the form of Greywolf’s (and later Lynx’s) alt.fan.furry FAQ, which was periodically republished as a new thread with updated definitions. The definition of “personal furry” first appears in a post dated March 1st, 1994:

WHAT IS A ‘PERSONAL FURRY’? Definitions range widely, but the common answer seems to be that a ‘personal furry’ is someone’s anthropomorphized animal “alter-ego”. This can mean a number of things: It could be a ‘furry’ character that the person roleplays on FurryMUCK (or some other roleplaying environment/game) that the person considers to represent him/herself. It could be an animal that the person is drawn as when represented in cartoons. It could be a person’s ‘totem’ or favorite animal type. One’s attachment to and attitude towards one’s ‘personal furry’ (if at all) varies greatly.

Greywolf’s definition gets at the polysemy of “personal furry” — that is, the multiple meanings that this word accrued as it was ever more ingrained in fandom discourse and thought. A neat similarity would soon occur on alt.horror.werewolves, whose members created were-cards, or phenotype descriptions of their were-selves. The key point here is that “personal furry” opened up explorations of one’s furry self — and these explorations happened across furry media.

1994: “Fursona” and Beyond

The earliest reference to the word fursona that I have found comes from a discussion on alt.fan.furry. In a June 1994 thread titled “Duckon” (referring to a sci-fi convention and MFF predecessor held near Chicago between 1992 and 2014), user Paul R Lester writes, “Duckon was a trip, even if I was only there one night. I got my first commissioned piece of art (a ‘fursona’ by Jim Groat), and got to see a number of people from AFF” (Lester).

Jim Groat explained to me that he started doing portraits of people as animal characters when attending an SCA [Society for Creative Anachronism] Ren Faire called Estrella Wars in 1990, along with the late Mark Wallace (aka “William Blackfox”), a respected artist who passed away in 1997.

So I started drawing folks in animal form, and since portraits were a new thing, I needed a catch phrase…So persona became Fursona. That clicked! Where Willie would be talking endless SCA stories while drawing, I was cranking out pictures. I was soon out drawing Willie. After two years of doing Estrella, I started showing up with my own tent pavilion and flogging the fursonas and SCA related T-shirts I produced.

(Groat, interview)

Ironically, Groat’s fursonas – possibly the earliest use of this term – are conceptually closer to the furry avatars of the 1980s, i.e., people in animal form. So while personal furry was morphing into what we now think of a fursona, fursona started out as something closer to an avatar. Crystal clear, right??

Despite the fact furries stick to consistent terminology about as well as fursuiters can open doors with big boofy paws, fursona took hold and eventually superseded personal furry. It’s unclear why, exactly, fursona emerged victorious, but it’s probably a combination of the fact that a) it’s a perfect portmanteau in a fandom obsessed with puns and wordplay; and b) it emerged just as the internet was starting to connect us all together. It’s no surprise, for instance, that just a couple years later, in 1996, users of alt.lifestyle.furry (a spinoff of AFF catering to self-described furry “lifestylers”) describe feeling spiritually connected to animal selves (shout-out to Shining River for their research assistance on this).2 Online furry art galleries, livejournal, and Yiffnet IRC (Internet Relay Chat) also got up and running around this time – the same time that conventions were also becoming more popular. Soon after, places like Luskwood on Second Life would start making graphic virtual realities possible for furries. In short, the furry world was ready to embrace the fursona.

How will the fursona evolve in the coming years? It’s anyone’s guess, but what’s always been at the heart of this concept is heart – a love of and bond with one’s OC. When he sets out to draw folks’ fursonas, Ken Sample told me,

I ask a *lot* of questions from the subject. I find a lot of the time, I ask them questions about aspects they didn’t ever think about. I think those situations is the person having to articulate something about themselves that just – is -. Never thought about it because it’s background. Foundational.

(Sample, interview)

If I’m lucky enough to meet the subject or know them, I try to display as much of their personality as possible with the image. It’s not just a dog that walks on two legs. It’s that person who is a dog that walks on two legs, plays the drums and loves to watch romantic movies and parties hard with the happiest laugh you’ve ever heard.

What’s more, several folks explained to me that their bond with their sonas has changed over time. Some folks get a new sona, or multiple sonas. For Reo GrayFox, who made both versions of his fursuit, “My suit and I slowly evolved. I learned and developed skills to continue to improve the looks of my suit to make it ‘feel right.’ I was become more comfortable being a Gray Fox. I was making a greater connection to the Gray Fox. […] I honestly believe that I did not choose Gray Fox. It was, in fact, that Gray Fox chose me.” Croc told me about how his sona has actually evolved over time:

At the beginning Croc was this ideal. You’re this perfect angel. That wasn’t fair to him. I wasn’t letting him have any flaws. Once I calmed down and let him be more real, he felt like a real being. When I let him have fragility and flaws, I could relate to him more. We became better friends at that point.

(Croc, interview)

Nowadays, there are even guides on how to make your fursona.

Whatever happens to fursonas, two things are beyond dispute: one, it is sure to be a fascinating and ongoing evolution; two, whatever new terms emerge or evolve, we will do a terrible job of clearly defining them. XP

Correction: the original version of the post referred to “Fanta” as Ken Coug’r’s mascot for the CF/O. Fanta is the mascot of the original C/FO in LA. Ken’s mascot for the C/FO NY is Anima, a winged feline.

Thanks & Works Cited

I’d like to thank Ken Sample for taking the time to answer all my questions across multiple forms of communication. I’d like to thank everyone else I interviewed and who gave me invaluable insights and connections: Croc O’Dile, Reo Grayfox, Wolf Kidd, Yippee Coyote, Fairlight/Dusk, Xydexx Unicorn, Jim Groat, Axiom Fox, Changa Husky, Uncle Kage, and Joe Strike. Huge shoutout to Brandy J. Lewis and Shining River for their research assistance!

Axiom Fox. Personal interviews (Telegram). March 8, 2024, and April 18, 2023.

Babcock, James E. “Snailmail.” Rowrbrazzle 10, ed. Marc Schirmeister (1986).

Benedikt, Claire and Dave Ciskowski. MUDs: Exploring Virtual Worlds on the Internet. Brady Games. 1995.

BunnyHugger. Comment on “Fursona origins,” a blog post by busybee. Comment published January 10, 2024. <link>

Crumb, Robert, Justin Green, Art Spiegelman, Shary Flenniken, Jay Lynch, Michael McMillan, and Bill Griffith. Funny Aminals. Apex Novelties, 1972.

Dr Luvstruk. How to Make a Fursona. E-zine. Dr. Luvstruck’s Laboratory, 2023. <link>

Croc O’dile. Personal interview (Zoom). April 14, 2024.

Dusk/Fairlight. Personal interview (Telegram). March 7, 2024.

Fay, Timothy, and Greg Bear. “The Kangaro Kaper.” Rowrbrazzle 3, ed. Marc Schirmeister (1984).

“Fursona.” Wikifur. Last updated February 29, 2024. <link>

Greywolf, Jordan. “Unofficial A.F.F. FAQ.” Alt.fan.furry thread. March 1, 1994. <link>

Gallachi, Steve. Albedo Anthropomorphics 8. Thoughts and Images. July 1, 1986.

Granger, KyiM. “Furverted Info.” Furversion 5, ed. Kyim Granger. November 21, 1987.

Groat, Jim. Personal Interview (FurAffinity). March 24, 2024.

Hill, Robert. “‘Don’t dream it – be it!’ Interview with Robert Hill about early fursuiting and fandom.” Interview by Patch O’Furr. Dogpatch Press. August 28, 2018. <link>

Lester, Paul R. “Duckon.” Thread on alt.fan.furry. June 5, 1994. <link>

Merlino, Mark, and Rod O’Riley. Two Old Furry Fans. Convention panel. PAWCon (San Jose, CA). November 4, 2023.

—— Episode 1. Two Old Furry Fans. Podcast. February 4, 2015. <link>

Siege. Personal interview (Telegram). 15 April 2023.

Stormi Folf. “How to Make a Fursona!” Youtube. February 24, 2019. <link>

Strike, Joe. Furry Nation. Cleis Press, 2017.

Weasel. “The Fandom: a White History.” Furry Book Review. September 16, 2020. <link>

Wolf Kidd. Personal interview (FurAffinity). April 7, 2024.

“Words We’re Watching: ‘Furry’ and ‘Fursona.’” Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2016. <link>

Xydexx Unicorn. Personal interview (Telegram). March 7, 2024.

Yippee Coyote. Personal interview (Telegram). March 7, 2024.

Reo Grayfox. Personal interview (Telegram). April 9, 2024.

Zaman, Hazel Ali. ” Furry acts as non/human drag: A case study exploring queer of color liveability through the fursona.” Queer Studies in Media & Popular Culture 8.3 (2023): 99-114.

- In researching, I couldn’t track down a record of a “Dragon’s Myth” BBS. I did find a BBS called “The Dragon’s Lair” from the 914 area code that operated 1982-1989 and was run by “Dragon Master” and his brother “Mike Spike.” http://bbslist.textfiles.com/914/ ↩︎

- See, for instance, this thread. ↩︎

I agree with the notion that the concept of the fursona isn’t really on the shoulders of one person, however it’s clear that someone like Ken Sample has had a massive impact on the movement. It was bound to happen, but that line of events early on really pushed things forward fast.

Out of transparency, I am friends with both Ken and Wolfkidd, but I think that qualifies me a little bit to agree with they are just a pair of fairly humble guys with ‘boring’ fursonas, lol. Honestly, that’s how they want it! They would much rather showcase their other characters, or the OCs of others, which tend to be far more fantastical by comparison.

Thank you for this article!

Thank you for reading the piece, as well as for this comment. I’m very grateful when folks chime in to share their experiences and knowledge. Writing about Ken’s influence was the hardest part to get right, and I agree with you that Ken had a massive impact — which I hope came across even as I wanted to respect his articulation of how he saw that history. Communicating with Ken and Wolf Kidd was really REALLY special for me as a furry historian and “lifestyler”. — Chipper

I had to look for myself that Merriam had “furry” on their “words we’re watching” list. They officially added both “furry” and “fursona” to the dictionary last September! https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/history-of-furry-and-fursona

Glad to see M-W saw the light. I wonder how long until UwU gets added?

folks forget that uwu comes from anime fandom!! that doesn’t detract from ur point, but still. context ||

A little embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know this! Thank you for teaching me!

This is an outstanding exposition on an important subject and point in Furry history. Understanding the nature of what we call “fursona” is key factor in understanding what makes Furry distinctive among popular culture fandoms and subcultures.

All of you reading this essay should appreciate the work Chipper put in to accomplish this task. A person can dig through the online sources without too much trouble IF one knows where to look and takes the time to sift throughout so many discontinuous posts and threads. It’s like trying to reconstruct an ancient Greek urn from shards scattered over many square meters of earth.

The interviews with our living Furry founders is the other outstanding part of Chipper’s essay. There’s nothing better than getting the story from the people who saw and made it happen. We have lost some of our old Furry founders. Sometimes we participate in the beginnings of cultural events, unaware of the significance our words and actions may have on the future. I hope that many more furries who are alive today will make some kind of literary and/or visual record of their contributions to our Furry community.

I am so grateful for your comment, Shining River, thank you. Reconstructing an urn from shards is a perfect analogy: this research involves so much digging, trying to make sense of the pieces, fit them into a coherent whole. But it’s incredible when that happens — and I have you to thank for helping me find some of those pieces!